The idea sounds reasonable

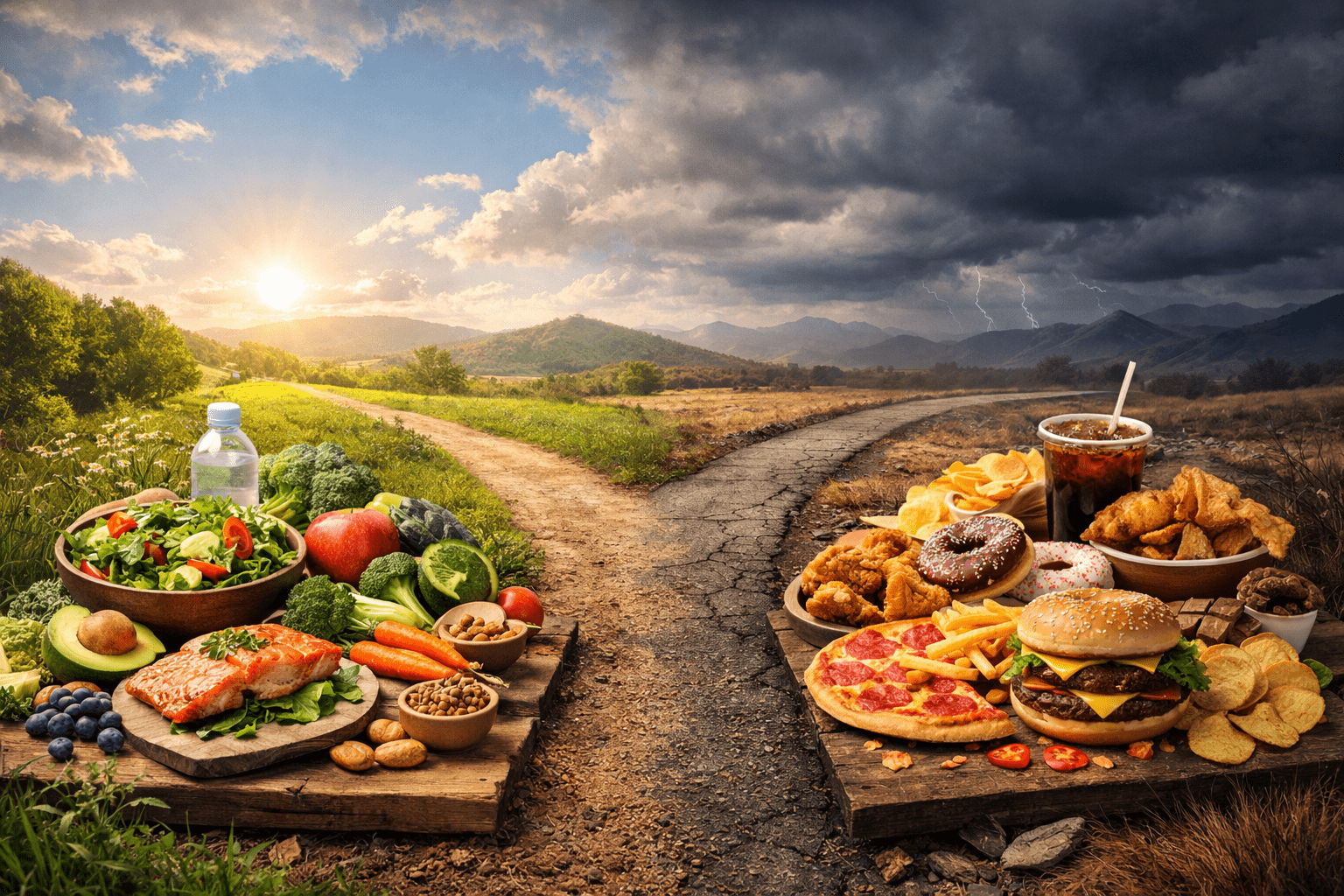

Most people don’t aim to eat perfectly.

They aim to eat balanced.

A little of everything.

Nothing extreme.

Moderation over restriction.

It feels sensible, mature, and sustainable — especially compared to rigid diets that rarely last.

And yet, many people who eat this way feel persistently off. Energy fluctuates. Weight drifts. Digestion feels unreliable. Health markers worsen slowly over time.

Not dramatically.

Quietly.

That gap between intention and outcome is the signal.

The common explanation blames execution

When a balanced diet doesn’t work, the explanation usually turns inward.

You misjudged portions.

You weren’t consistent enough.

You let treats creep in too often.

Sometimes that’s true.

But it doesn’t explain why people who are genuinely attentive, disciplined, and informed still struggle — even while doing exactly what balance prescribes.

The problem isn’t effort.

It’s the environment balance now operates in.

Balance worked when food environments were simpler

“Everything in moderation” made sense when:

-

food was minimally processed

-

ingredients were limited

-

meals were infrequent

-

hunger cues were intact

In that context, variety didn’t overwhelm the system. Moderation had natural boundaries.

Modern food environments removed those boundaries.

Today, balance often means rotating through dozens of refined inputs, engineered for palatability, available constantly, and consumed without natural stopping points.

Variety no longer protects.

It amplifies exposure.

Why balance quietly increases cognitive load

A balanced diet requires constant judgment.

Is this enough protein?

Did I earn this?

Can I offset that later?

Each decision feels small. Together, they create friction.

The body experiences this as inconsistency. The mind experiences it as low-grade vigilance. Neither state supports stability.

Over time, balance becomes a moving target — not a steady system.

And systems that require constant adjustment rarely hold.

The hidden cost of nutritional flexibility

Flexibility is often praised as the antidote to rigidity.

But flexibility without constraints tends to drift.

When no foods are excluded, the most convenient, palatable options win more often than not. Not because of weakness — but because they’re engineered to.

This doesn’t lead to collapse.

It leads to slow metabolic confusion: disrupted appetite signaling, erratic energy, and difficulty maintaining baseline health without increasing effort.

Balanced diets fail not by excess.

They fail by accumulation.

Why some people “thrive” on balance anyway

This is where confusion deepens.

Some people eat flexibly and appear unaffected.

Usually, they have buffers:

-

higher muscle mass

-

fewer meals

-

simpler routines

-

earlier exposure to healthier baselines

Balance works when exposure is low.

Once exposure rises, balance becomes permissive rather than protective.

What capable people tend to notice earlier

People who maintain stable health over long periods rarely eat “everything.”

They reduce variables.

They repeat meals.

They narrow choices.

They prioritize predictability over novelty.

Not because they lack discipline — but because they understand how quickly modern balance erodes consistency.

They don’t chase perfect nutrition.

They build systems that require less negotiation.

Why this mirrors other modern failures

The pattern is familiar.

Just as “balanced spending” fails in an inflationary system, balanced eating fails in a degraded food environment.

The rule didn’t break.

The context did.

A clearer way to see balance

Balance isn’t wrong.

It’s outdated.

It assumes inputs that no longer exist at scale.

The more useful question isn’t “Am I being balanced?”

It’s:

“What does this system reward when I’m not paying attention?”

That answer determines outcomes far more reliably than good intentions.

And once seen clearly, it quietly changes how people eat — without requiring rules, guilt, or extremes.

0 Comments