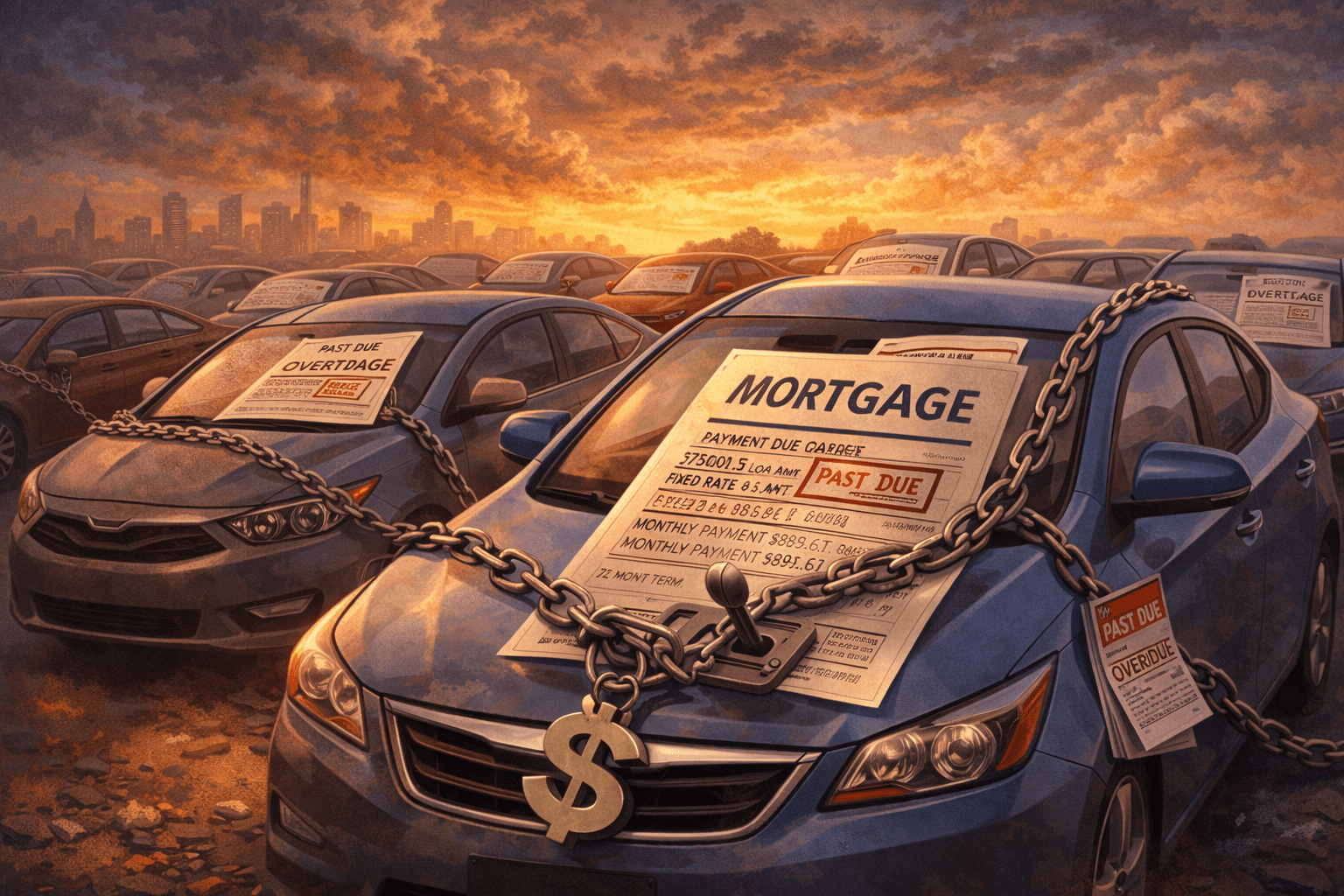

The shock isn’t the sticker price — it’s the commitment

Most people don’t expect a car to feel like a life decision.

And yet, that’s what it’s become.

Seven- and eight-year loans.

Monthly payments that rival rent.

Vehicles that cost more than what homes once did.

It’s not just that cars are expensive.

It’s that buying one now feels like stepping into a long-term obligation — one that quietly narrows future choices.

That sense of weight is new.

The usual explanations miss the point

Rising car prices are often blamed on supply issues, technology, or consumer taste.

Chip shortages.

Electric transitions.

“People just want nicer cars.”

Those factors exist.

They don’t explain the full picture.

If this were only about features or temporary constraints, prices would correct. Terms would shorten. Risk would remain manageable.

Instead, debt stretched to accommodate prices — not the other way around.

That’s the signal.

When mobility turns into long-term debt

Cars were once consumables.

They depreciated.

They were replaced.

They didn’t define financial identity.

Over time, that changed.

As prices rose faster than income, financing absorbed the pressure. Loan terms lengthened. Payments normalized. The purchase stopped feeling temporary.

Mobility — something meant to increase freedom — became a fixed obligation.

And fixed obligations quietly reduce optionality.

Why repossessions are rising even without panic

What’s striking about current repossession trends isn’t chaos.

It’s calm.

People aren’t reckless.

They’re overcommitted.

A small disruption — job change, expense spike, rate increase — is enough to trigger failure because there’s no margin left.

This isn’t about irresponsibility.

It’s about systems that require perfection to remain stable.

Those systems always fail eventually.

The hidden role of signaling

Cars don’t just move people.

They communicate status.

As housing slipped out of reach for many, vehicles quietly absorbed some of that signaling pressure. Bigger, newer, more expensive cars filled the gap — often unconsciously.

The problem isn’t vanity.

It’s substitution.

When traditional milestones move away, people reach for visible proxies of progress. Debt makes that possible — briefly.

Why “just buy cheaper” isn’t the solution it sounds like

Advice to simply downgrade misses the structural issue.

Affordable options shrank.

Used prices rose.

Repair costs increased.

Even restraint now requires tradeoffs that didn’t exist before.

This isn’t a failure of decision-making.

It’s a compression of viable choices.

What capable people tend to notice earlier

People who stay flexible treat cars differently.

They see them as:

-

tools, not upgrades

-

costs to be bounded, not justified

-

commitments that shape future freedom

They’re less concerned with monthly affordability and more concerned with exit cost — how easily they can unwind the decision if conditions change.

That lens makes the difference.

How this fits the larger pattern

This isn’t just about cars.

It’s about what happens when:

-

currency weakens

-

assets inflate

-

income lags

-

debt fills the gap

Housing became unreachable.

Cars became leveraged.

Optionality shrank.

Each system absorbed pressure until it couldn’t.

A clearer way to see it

The problem isn’t that cars cost more.

It’s that they demand more certainty than modern life provides.

When a depreciating asset requires a decade of stability, something in the system is misaligned.

The better question isn’t “Can I afford this payment?”

It’s:

“What does this obligation quietly limit over time?”

That question doesn’t make cars cheaper.

It makes their true cost visible.

0 Comments